WW1 series. Where the Great War shook the Earth; the story of the Lochnagar Crater.

/Some historians of World War One have stated that any tour of the Battle of the Somme area should start with the Lochnagar Crater. (The background to the Battle of the Somme is outlined in more detail below). It is a massive crater, one hundred metres (328 feet) in diameter and 30 metres (98 feet) deep. Why on earth was it made or rather, how on earth was it made?

It was created by the British, when two batches of explosive, 16 metres deep and 20 metres apart, went up at 7.28 am on July 1st. It was hoped that loads of the enemy near La Boiselle, would be killed and others would be stunned and not know what was going on. This, along with another eighteen mines, was the signal for men to “go over the top”, ie get out of their trench, make their way through the already cut barbed wire protection and then run at the enemy. The Germans were supposed to be killed or at least, so dazed that the British would quickly take control. Sadly, the British soldiers were to walk into machine gun bursts as well as artillery shells and stood little chance of surviving, let alone reaching the enemy trenches.

What can you see at the Lochnagar Crater?

Below as you approach the crater this cross comes into view. This was made from medieval timbers from a deconsecrated church near Durham which is very relevant because many of the soldiers killed, were from Tyneside.

Below: A boardwalk around the crater makes walking easy and giving a 360 view of the sheer scale of this scar on the landscape. One can begin to envisage a vast cloud of soil and rock, covering the sky. It must have been as though the world was coming to an end.

Below: Information boards are situated all around the crater giving a comprehensive understanding of what has happened here.

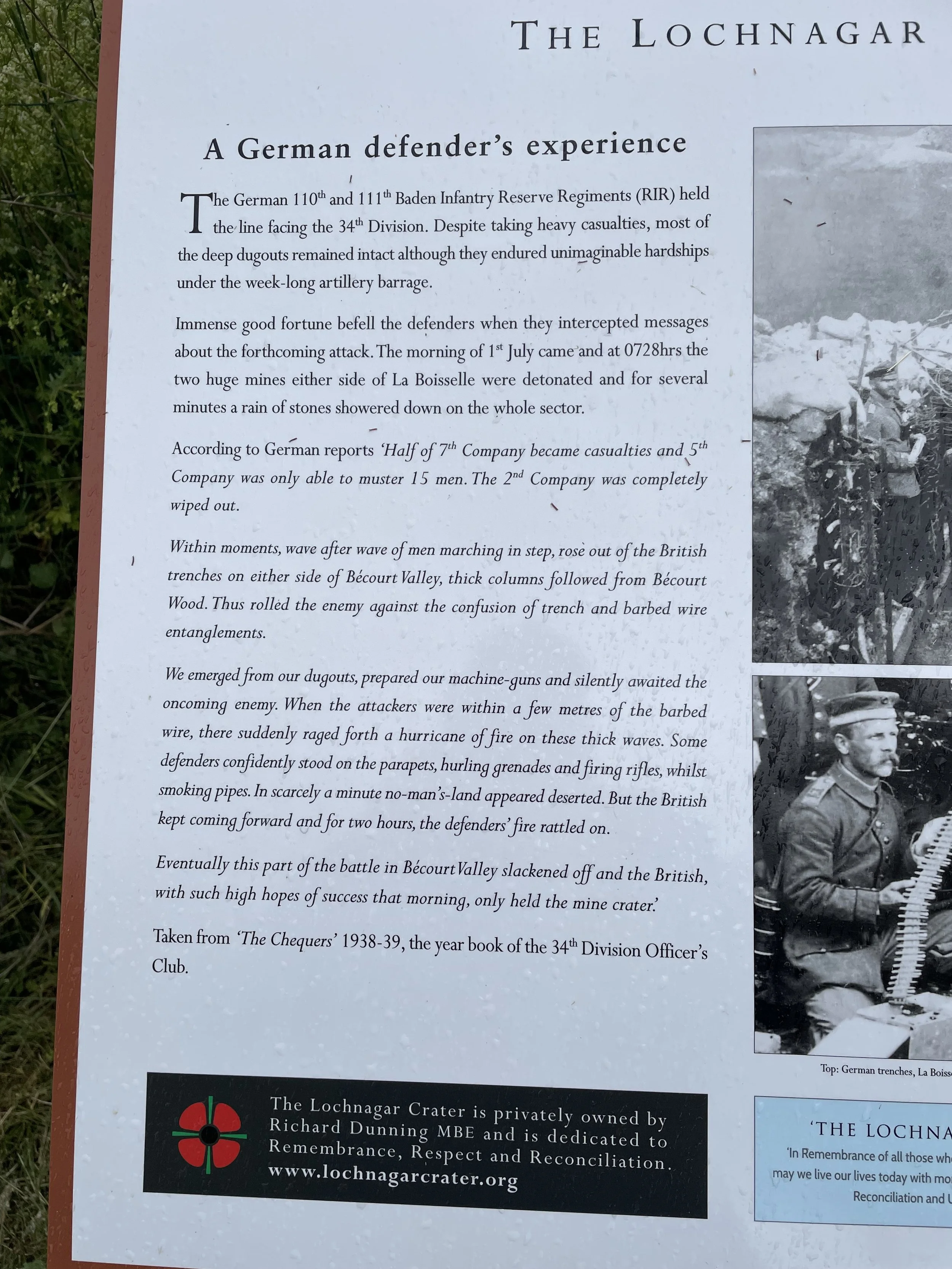

Below. The next two photos show an information board that gives the reader a German defender’s experience.

Below: Some of the boards have sponsored plaques with the names of people associated with the Battle of the Somme and, in some cases, the names of the people or institutions who paid for the plaques.

Below: A cross bearing the name of Private George Nugent. After the war his body had not been found and so his name was put on the Thiepval Monument for the missing. However, he was found buried at this spot in 1998 along with his razor. His razor had a service number stamped on it and from that they discovered his name. It was tradition that no soldier ever borrowed a razor from another soldier and so it was deemed that this must be George Nugent’s remains. He was reburied, with military honours, nearby, at Ovillers Military Cemetery on 1st July 2000, 84 years after he was killed in battle.

Below: A little memorial to women who served in World War One.

Below: Poppies adorn the surrounding fields.

Below: Wild flower seeds have been sown around the crater including this beautiful orchid.

The Lochnagar crater was created at the start of the Battle of the Somme but what was the Battle of the Somme?

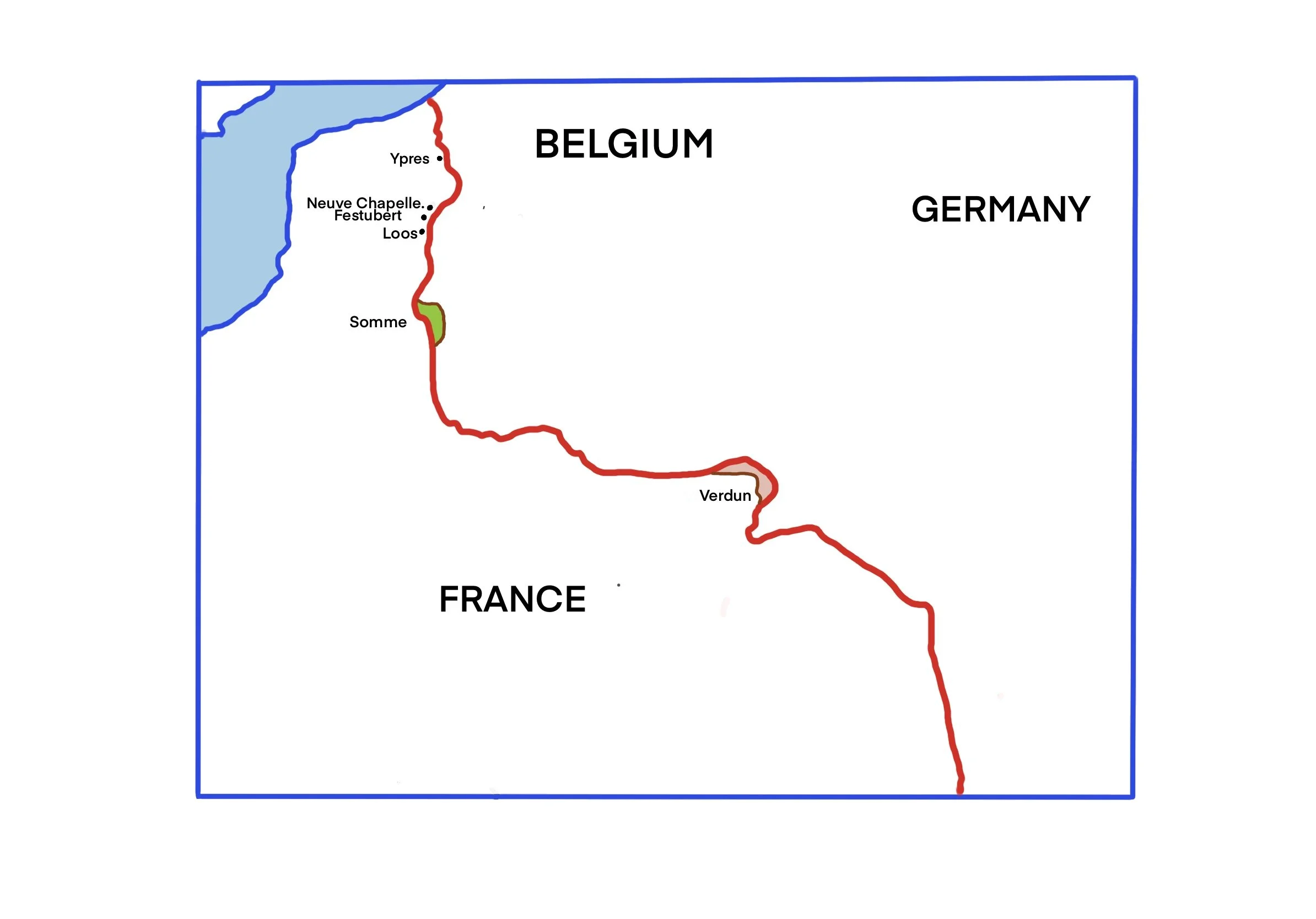

By the end of 1915, there was a a continuous line of trenches from the North Sea to Switzerland with neither side gaining or losing territory. In other words , despite their best efforts, there was “stalemate”. In March 1915, the British attacked Neuve-Chappelle and despite capturing it, did not make any further advances. In April 1915, the Germans attacked at Ypres in Belgium using poison gas but their gains did not last long. The British and French launched battles of Festubert, Aubers Ridge and Loos but again no substantial breakthroughs were made.

A new front was opened up against the Ottoman Empire, allies of Germany and Austria. What became known as the “Gallipoli Campaign” fought by British, Australian and New Zealand troops against Turkish troops (Ottomans) ended up in a complete allied disaster with 189,000 men dead, wounded, missing and captured.

However, a high level meeting at the end of the year resulted in plans for a fresh start by fighting a massive battle consisting of British, Empire and French troops across a large front. For co-ordination of the allies, the area to be attacked was to be the River Somme, the place where the allied armies were adjacent to each other ie the British and Empire troops were to the west and north, whilst the French to the east and south.

Unfortunately, the Germans were also planning for advances in 1916 but in their case, it was to concentrate huge forces at Verdun and its historic fortress. Their idea was that the French would be so desperate to stop the Germans capturing the area that they would keep defending it, no matter how many lives were lost. With the French severely weakened, the Germans could then switch focus to beating the British, Empire and Belgian armies.

The Battle of Verdun began at the end of February and soon began to be catastrophic for the French. As a consequence, the French part of the plan for the Somme was dramatically reduced. The British and Empire troops now had to attack so successfully that the Germans would have to remove troops from Verdun to prevent a British breakthrough. This would relieve the French at Verdun. An Allied victory was essential to prevent a German breakthrough into open country and disastrous consequences.

What is the story of the Lochnagar crater?

Below is a information board which illustrates how tunnels were made for the mine were made.

The tunnels were dug to a point under a German strongpoint known as the “Schwaben Hohe”. Work was started on 11 November 1915 by 185th Tunnelling Company, and was completed by 179th Tunnelling Company who took over in March 1916. The mining consisted of 4 shafts down to a depth of 35 metres. begining 120 metres behind the British front line and 300 metres from the German front line. An inclined shaft was dug at an angle of 45° to a depth of 35 metres and then two horizontal shafts were created, although only one was eventually used. Digging through chalk silently was not easy. The mining had to be quiet to ensure that the germans were unaware of what was being planned. This meant they had to use bayonets and was a very laborious task. The miner at the chalk face would lodge the bayonet in a crack or next to a piece of flint and twist it to dislodge a chunk of rock. The piece of chalk or flint would be caught by the second miner who put it in a bag and passed it along a line of miners. The miners had to endure a ceiling of 1.4 metres in a shaft, 0.8 metres wide. Added to this, the miners had to work in bare feet on a floor covered by sandbags. Progress was made at an average of 5 metres a day. This produced about 48 sandbags full of chalk to be arduously removed every day. At the end of two shafts, explosives were placed 16 metres below the surface and 32 metres short of the German front line. The two sets of explosives weighed a massive 24, 000 lbs and 36,000 lbs (27 tons). No wonder people in England claimed that they heard the explosions.

The mine went off exactly as planned. The German stronghold, the “SchwabenHohe” (Schwaben Heights) south of the French village of La Boiselle, was now severely weakened. The mine was to be the second to last piece of the plan. Initially, several days of artillery fire would have destroyed German trenches, killed loads of soldiers as well as their equipment and above all, would have blown to pieces their barbed wire.

It was estimated that soil and debris were blasted over 1000 metres into the air and then rained down on the Germans, burying many alive. It had obliterated between 91-122 metres of German dugouts supposedly full of German soldiers but this wasn’t the case. After the war, experts have suggested that the Germans usually didn’t pack out their front line trench but preferred to keep the majority behind them to avoid initial artillery and mine attacks. They have also pointed out that unbeknown to the British, German second and third line trenches were a lot deeper, being up top 10 metres deep and therefore resistant to artillery fire.

As the soil came down some of it created a rim around the crater over 3 metres high which protected the advancing British troops from the German machine guns in the village of La Boiselle. The rim was caused by a process called “over charging” ie enough to blow a hole in the ground but with extra to spread the soil around the surrounding fields. This success was countered by troops to the left and right of the crater that fell to small arms fire and artillery.

Did the Germans know about the British plans?

Yes. The Germans were aware of an attack had been planned and despite British efforts, they were also aware that the British were digging mines.To counter the British, the Germans dug their own mines and discovered that the British were nearby! After the attack, the British discovered that they got within 2 metres of the German counter tunnel!

What happened to the men who were to fight near the Lochnagar crater?

The men who were to fight in this area were all from the 34th Division which was made up of “the Pals Battalions”. They were given this name because they were made up of men who knew each other before signing up. The recruitment theory was that men were more likely to sign up if they fought with people who were known to each other, from their local area, rather than complete strangers. Many of the soldiers would have been to school together and possibly worked together or played football together. It also would mean that they would encourage each other to sign up. This attack would involve the 15th and 16th Royal Scot’s Battalions, the 10th Lincoln’s aka “The Grimsby Chums”, the 11th Suffolk’s aka the Cambridge Pals, the 21st and 22nd Tyneside Scottish and the 20th Tyneside Irish.

Private Charles R Frankish of the 10th Lincolns (the “Grimsby Chums”) wrote this account of what happened to him;

““It seemed a long wait until 7.28am when the mine went up. I remember the ground shaking like a jelly. We had been told that the advance would be a walk-over, as the trenches had been destroyed and most of the troops killed but we knew this was not true, as several times before the attack we had shown our dummy troops over the parapet, (tunics filled with straw and wearing gas masks and tin hats). The reply was a terrific hail of machine-gun and rifle fire.

After two minutes we went over the top into the churned mud of no-man’s-land.

The small arms and shell-fire was very heavy. I had not gone far when a bullet struck my equipment and spun me round like a top, but I was none the worse. It was very hard going as I was also carrying two trench mortar bombs in a sand-bag.

About half way to the German trenches I received a terrific blow on my left forearm.

I collapsed into the nearest shell hole, my arm quite useless, apparently broken.

Eventually I made it to No. 102 Field Ambulance Station to enjoy the best sleep I had had for months.” ”

From a fighting strength of 840 men, the Grimsby Chums suffered over 500 casualties of which 180 were killed whilst trying to advance 450 metres. In all, 75% of these men became casualties! The Scottish Tyneside’s had 365 metres to get across to the Germans but the land in front of them was flat and they were easy targets for German machine gunners.The Irish’s target was 730 metres from their own front line but they were positioned a mile behind the front trenches and so had even further to travel and be targets! Despite this a small group did achieve their goal but were not supported on either side and so had to retreat.

Troops advancing in the Battle of the Somme. IWM non commercial licence.

Reliance on a seven day artillery barrage was flawed.

Any of these battalions getting a glimpse of the German front line would also have noticed that the mass of barbed wire in front of the German front line had not been destroyed. The commander’s belief in the effectiveness of artillery had proven to be wrong. Why was this? The British had had to use quickly trained people to manufacture shells to overcome a large shell shortage. Shell fuses were complicated mechanisms and normally a lengthy training period was used to produce shells that regularly worked. Thirty three percent of the shells failed to go off. In the Battle of the Somme, 500,000 out of the 1,500,000 shells failed to go off. Furthermore, the British had far more shells that went off scattering ball bearings everywhere as an anti-personal weapon. Unfortunately, the ball bearings missed the barbed wire as they flew in every direction or simply bounced off it. High explosive shells were far more effective but were limited in supply.

They high command did learn from this and in September tanks were used. In the five month battle, 3 million soldiers were used from both sides and 1 million casualties resulted. Sadly, July 1st, has gone down as the worst day ever for the total number of British casualties. It resulted in 57,000 casualties out of which, 20,000 were dead across the Somme front line.

The battle eventually concluded in mid November with the British Empire and French forces gaining an average of 6.2 miles of German held territory along most of the front line. This was their largest gain since 1914 but they did not capture all of their objectives and did not bring the end of the war closer. It took until November 11th 1918 to bring about peace.

Essential information

Getting there.

I advise to visit by car which will allow you the visit other fascinating places nearby. There is a small parking area . The Lochnagar Crater Foundation gives the following information:

The Lochnagar Crater is within the Commune of Ovillers-La Boisselle, just south of the village of La Boisselle.

Take the D929 between the town of Albert and the village of Pozières. On arrival at La Boisselle look out for the signs to the La Grande Mine.

In La Boisselle, follow D20 for a short stretch and then turn into the Route de Becourt, going immediately left at the Y-fork.

The Crater is a short way along a no through road name Route de la Grande Mine.

WARNING: Some navigation apps will show a route from Fricourt directly to the crater. This road is NOT accessible for motor vehicles.

Using the road through the village of La Boisselle is the only option!

Please note there are NO public toilet facilities at the Crater or in La Boisselle village, but of course the local cafés have facilities for their customers. (On-site toilets are available at the Crater on event days).

Rising from the quiet countryside of the Somme, the Thiepval Memorial stands as one of the most powerful reminders of the First World War. Built to honour more than 72,000 British and South African soldiers who died in the Battle of the Somme and have no known grave. Designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, the memorial is not just a monument of stone, but a symbol of absence, loss, and remembrance. Its vast arches and engraved names speak for those whose bodies were never recovered, giving them a place in history and in memory.