Understanding Sacrifice: An Educational Experience at Vimy Ridge

/Stepping onto the grounds of Vimy Ridge is to step directly into one of the most defining moments in Canadian military history. As we walked through the remarkably preserved trenches, wandering past numerous bomb craters and stood beneath the soaring limestone pillars of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, the story of the 1917 battle came vividly to life. It was here, during the First World War, that the four divisions of the Canadian Corps fought together for the first time and achieved a hard-won victory against formidable German defences—a success earned through meticulous planning, innovation, and immense sacrifice. So many craters can only be explained by massive artillery bombardments from both sides and what readily can be described as “Hell on earth”. Today, the quiet fields and powerful memorials serve not only as reminders of that pivotal battle, but also as lasting symbols of Canada’s courage, unity, and emerging national identity. We have been here numerous times and have noted the solemnity and peacefulness of the area. Vimy Ridge has often been our first stop on a school trip and our young students have commented on the peaceful atmosphere.

What can you see at Vimy Ridge?

Below; your first view of the preserved trenches. The Canadian flag is where you meet for a guided tour of the trenches and one of the tunnels. Your guide will be a well informed Canadian student who will not be afraid to be asked questions. In the distance, the grey line is the Canadian trench. You can climb into these trenches and walk along them. You will naturally look over the top to the opposing trenches but remember, “as quick as a flash” you would have been shot by an enemy sniper, waiting for a target to appear.

Below: is an information board map showing where all the vast craters are located. These were made by German and British miners with the aim of adding to their defences ie. making a large crater next to an enemy trench so that it is not easy for them to stage an attack. They would either have to run down into it and up the other side which would be suicidal, or traverse along narrow paths between the craters and then be an easy target.

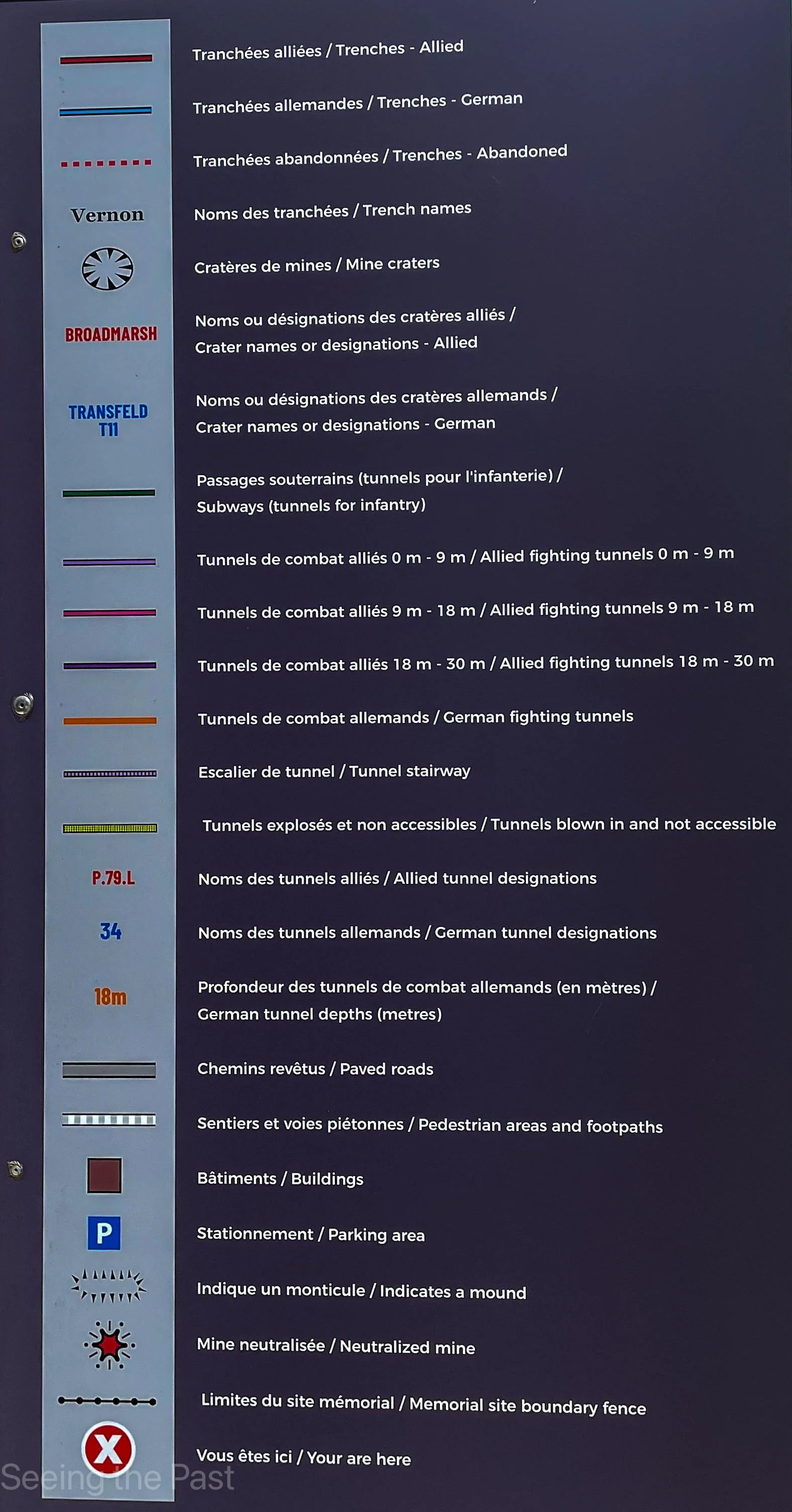

Below: a brief explanation of what all the symbols represent.

Below: one of the large craters between the two opposing front lines. The two people you can see are in a German observation point which would be used to spy on the enemy, who was Canadian in 1917. They were there to spot and report on all enemy activity, small raids or large attacks. The Germans could also launch their attacks or raids from these points being closer to the enemy. Raids might be for information gathering or to capture prisoners who would then be interrogated for information. The crater would have been caused by a mighty underground explosion which would have been deafening. Before and during an attack, the artillery shelling going on for hours would also be deafening as well as leaving the men in the trenches fearing that they might be the next target.

Below: A German machine gun post.

Below; the trenches were designed to have many sharp turns so that if a shell explodes in one or nearby one the effects of the blast are limited in scope ie soldiers around the next bend have a lot of earth between them and the shell burst to absorb the effect of the explosion.

The walls would not be made with concrete sandbags but actual sandbags, wooden planks or sheets of corrugated iron. Waiting for the next attack would be boring although soldiers would become aware of rats looking for food which in some cases was a body in no man’s land! The men would have an urge to scratch their body because body lice were a constant companion. We can only start to imagine what the men were suffering whilst stationed in these trenches. Simply standing in cold, water filled trenches could make their wet feet start to rot resulting in a common illness called “Trench Foot”. This would eventually lead to gangrene if not treated.

Below; to give you an impression of what a trench here was like, here is Richard in a mock up trench at the Passchendaele Museum in Zonnebeke. Belgium. He was in his normal clothes but I asked Ai to put him in WW1 uniform with an appropriate rifle.

Below:the view from the Canadian frontline trench across to the German trench. The arrow on the right is pointing at the machine gun post. The arrow on the left is a German observation post. They are about 40 metres apart. Note the large craters between them to make attacking difficult.

Standing or sitting in a muddy trench waiting for something to happen was very boring. One lapse of concentration with a soldier putting his head out of the trench could result in instant death from a sniper’s bullet. A seemingly long period of doing nothing could be replaced in a few seconds when an attack took place which could also be exhausting. To keep their troops ready for action should an attack be spotted meant that recuperation behind the lines was very important and thus, contrary to popular belief, troops would only spend about 20 per cent of their time in the trenches.

Below: away from the preserved trenches, shell craters can be seen in every direction. The only flat pieces of land are modern constructs.

Below: in the summer, Canadian students conduct free guided tours of one of the tunnels that were created in order that troops could secretly make their way to the front line without being seen by the Germans. As you can see from the next three photos, there is very little room for tourists let alone soldiers with all of their equipment and a long rifle with a fixed bayonet.

Over 10 km of tunnels were dug for the Canadian assault on Vimy Ridge. Apparently, the miners dug 6 metres of tunnel a day with each metre of tunnel resulting in 200 sandbags of chalk having to be removed.

Below: a photo from the top of the ridge showing the Douai plain below and why the ridge was important for its commanding position.

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

Below; an aerial photo of the Canadian Memorial. The Memorial was built on the highest point which was the target of some of the Canadian forces. All around the Memorial are shell holes which made it incredibly difficult to get to the objective, ie the high point. Soldiers had to clamber from one hole to the next whilst being shot at and shelled. Inscribed on the white stone are 11 285 names of the dead soldiers with no known grave.

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Below; as you get closer to the memorial you will be able to see some amazing sculptures.

Below: the next five photos show the sculptures in more detail.

Below: a map showing the progress made in three stages , beginning in 1914 and then the big breakthroughs in 1917 and 1918 with the end in November 1918.

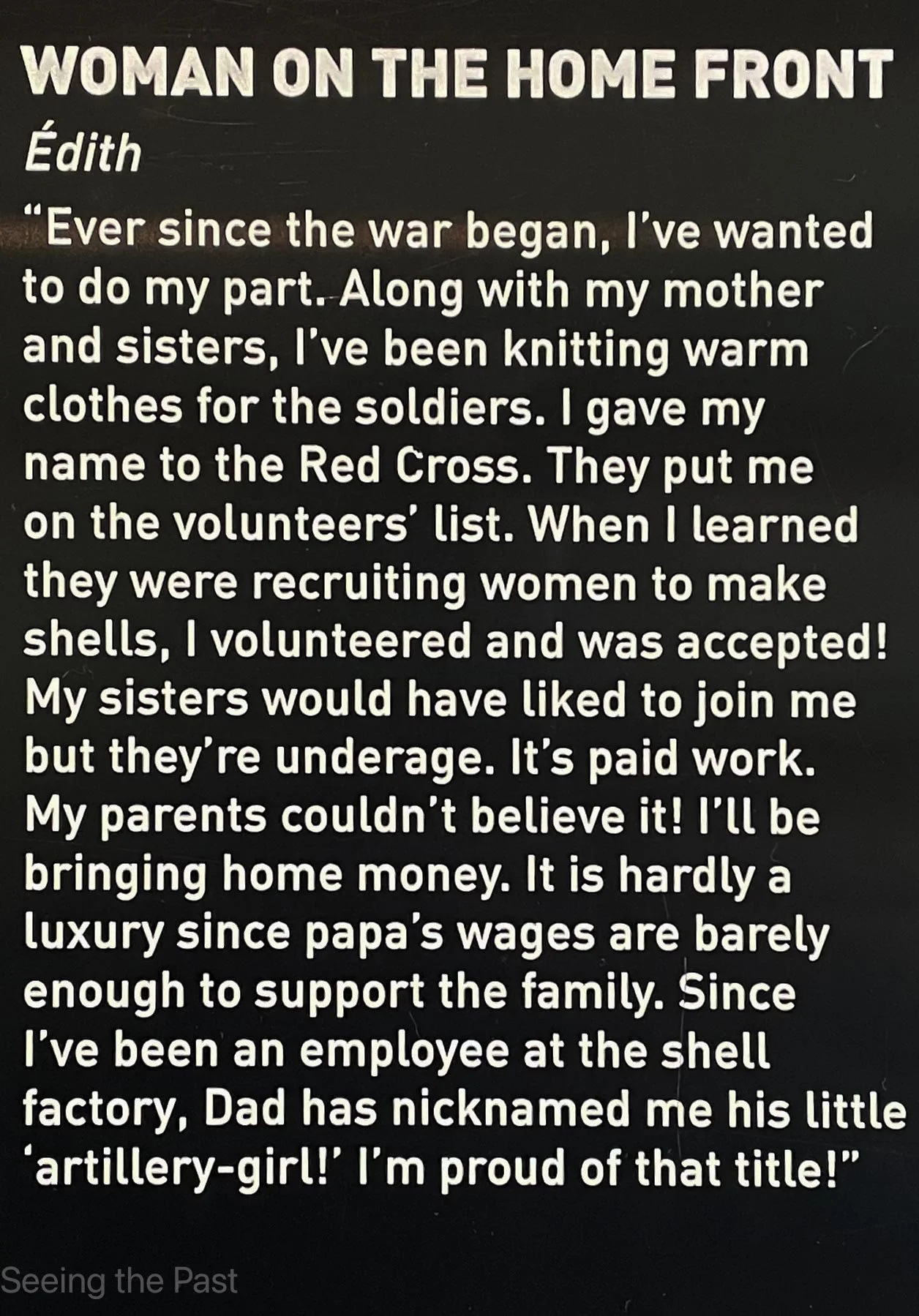

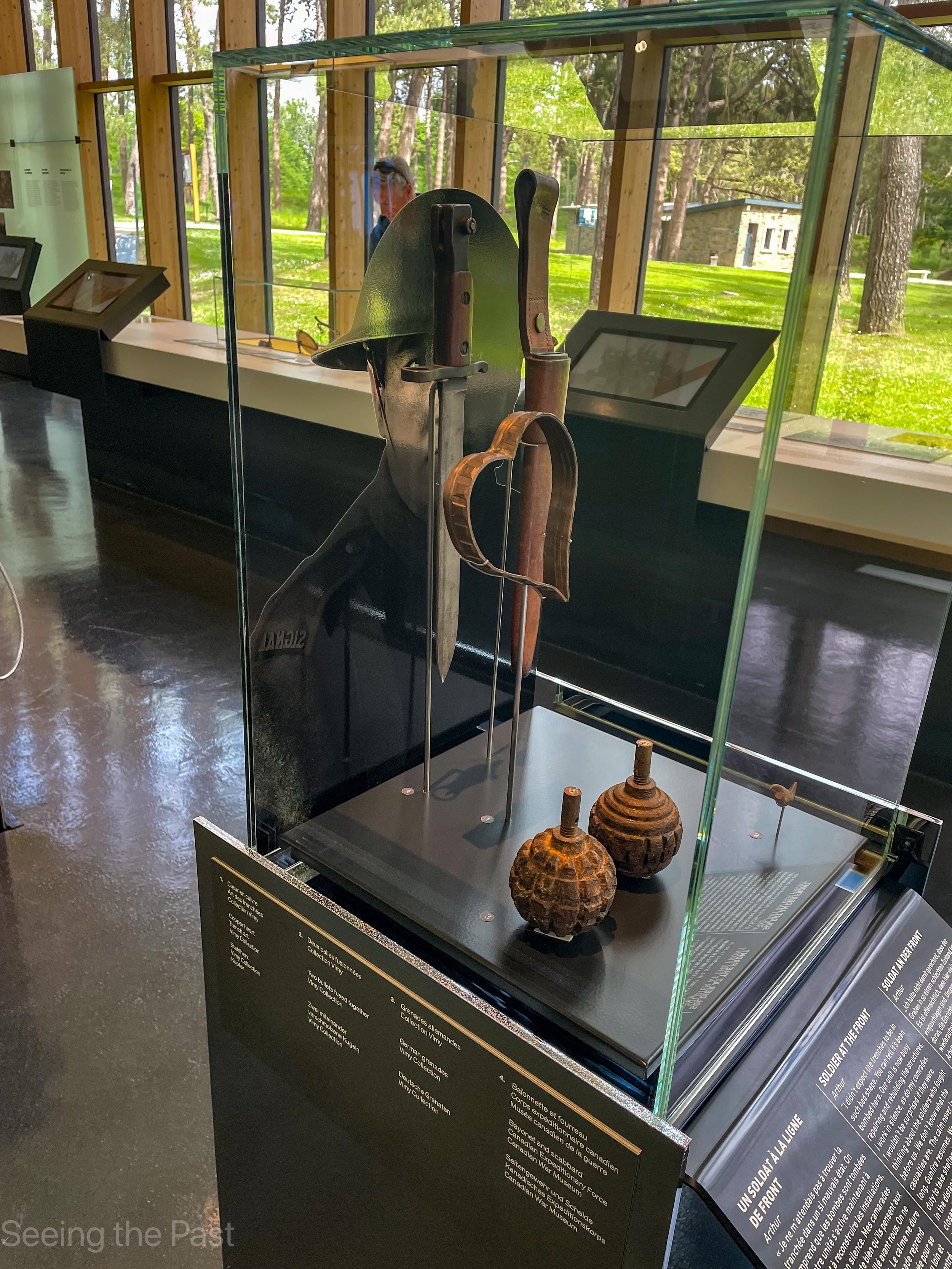

Below: In the Visitor Centre there are numerous fascinating things to see and read. This case contains a fused shell as well as a photo of a female shell maker. Below this photo is information to go with the case.

What happened at Vimy Ridge?

In 1914 this area had been occupied by the Germans and, initially, French troops were expected to push them back. Walking from the visitor centre towards the Canadian Memorial, the trenches that you will see running through the trees were French trenches from that period. The French North African troops nearly succeed in capturing the ridge but were eventually pushed all the way back.The British took over but failed to reconquer the Vimy Ridge highland.

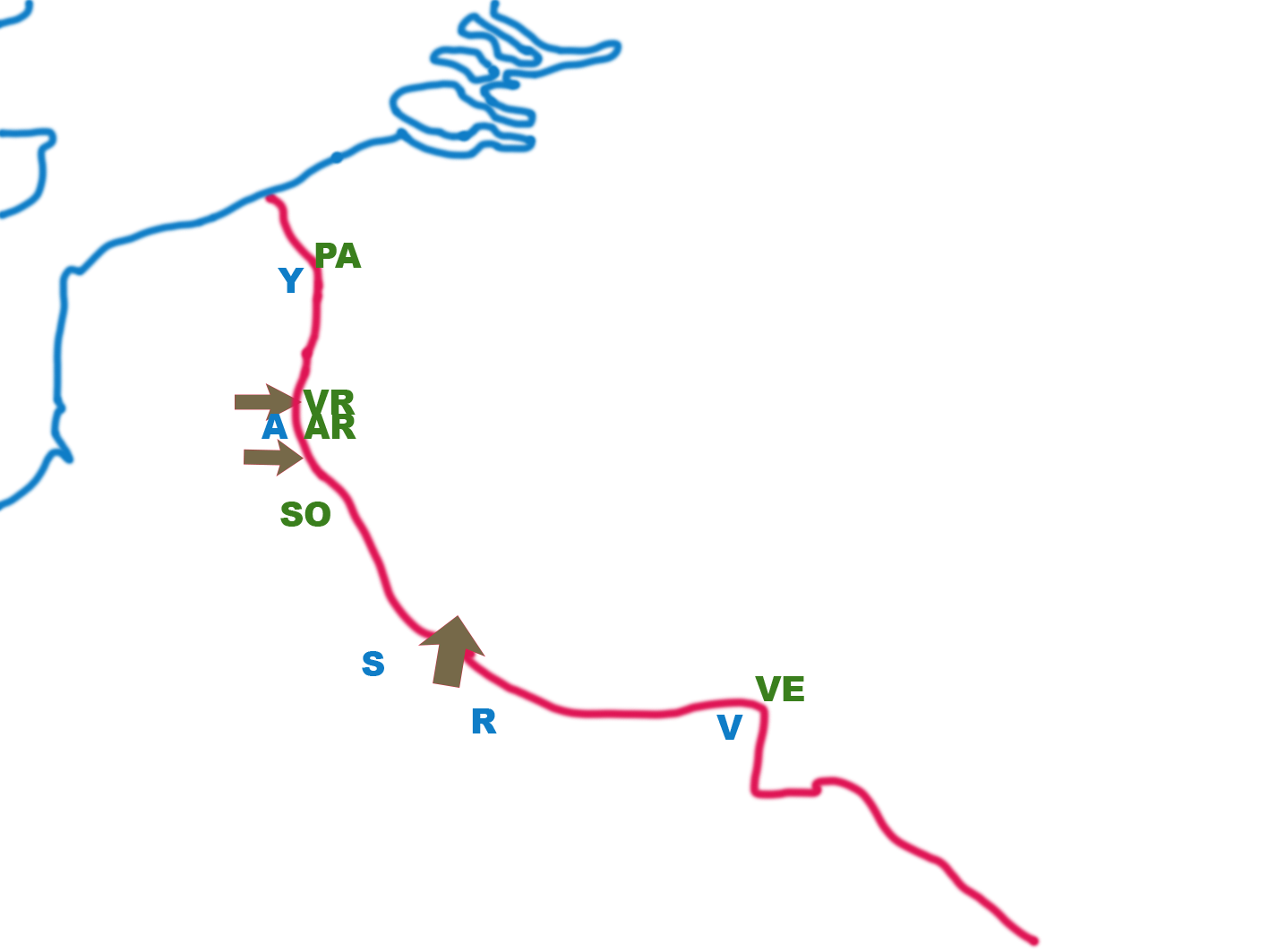

Below is a sketch map of the “Western Front” with, on the left, the British Empire troops and the French, and on the right, the German troops. On the map below, blue letters stand for the towns of Ypres, Arras, Soissons and Verdun. The green letters stand for battles, Passchendaele, Vimy Ridge, Arras, Somme and Verdun. The brown arrows indicate where attacks were going to be made. In 1917, the French wanted to mount a 30 km wide campaign between Soissons and Reims but needed to divert German attention away to the north-west. An attack by the British at Arras a week before the planned French attack would succeed in diverting the Germans but for the British attack to succeed, the British would need to take out the Germans to the north of Arras, at Vimy Ridge. This was a commanding position on Vimy Ridge where they could see everything happening and give locations for their artillery to shell. The highest points on this 8 km ridge were known as Hill 145 where the Canadian Memorial is today and to the north, “The Pimple”. If the Canadians were successful at Vimy, the British would be successful at Arras and so draw German troops towards them, thus allowing the French attack in the south to be successful. If the Canadians were unsuccessful, the rest of the plan would not work.

The job was given to four Canadian Divisions, making up 120, 000 men. The British were there to help with artillery support, an essential part of the plan for it to succeed. When compared to what happened on the first day of the Somme, not even a year earlier, events turned out very differently, although Vimy was still costly in terms of the number of dead and wounded.

This time the troops were well trained and informed with regards what they had to do. Some training was done with scale models and numerous maps were issued in order that the men knew the location of their target in the height of battle. Underground tunnels were to play a part too, in that, men and ammunition were able to covertly move up to the front line .

The major difference between the Battle of the Somme initial attacks and those of Vimy Ridge was that an accurate artillery creeping barrage was carried out and succeeded as planned. Maps were created with lines and times for barrages to take place followed by men moving forward. The barrage moved just ahead of the attacking troops forcing the Germans to keep low to protect themselves. By the time the barrage lifted from a particular German line, the Canadians appeared and were able to take out any surviving enemy just in front of them.

At 5.30 am on 9th April 1917, 850 artillery guns shot into the air and from then consistently moved their target 100 yards forward every 3 minutes. For extra encouragement, bag pipers from the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry played as the first men charged into “No Man’s Land”. Targets were reached, even with snow falling at one stage. The shell fire ripped up the land so much that it was hard to move forward but determination, training and their preparations got them through it all. To make matters worse, many brave German stayed with their machine guns spraying the area with bullets rather than move back as expected. These too were overcome by determination and Canadian courage. Machine guns on “The Pimple” caused heavy losses on the flank of the advancing Canadians but again they carried on. Some combat was hand to hand from waterlogged shell hole to waterlogged shell hole but somehow on the next day the Canadians had secured the ridge and Hill 145.

Figures vary but it is thought that Canadian and British deaths totalled 3600 and with 7000 casualties. German casualties are thought to be 7000 dead and wounded with 4000 men taken prisoner. All the Canadian troops can be considered as heroes for attaining their goal but Thain Wendell MacDowell, Ellis Wellwood Sifton, William Johnstone Milne and John George Pattisson went “the extra mile” and were awarded the VC. To give an idea with regards to what they did, John George Pattison’ citation stated:

“For most conspicuous bravery in attack. When the advance of our troops was held up by an enemy machine gun, which was inflicting severe casualties, Pte. Pattison, with utter disregard of his own safety, sprang forward and, jumping from shell-hole to shell-hole, reached cover within 30 yards of the enemy gun. From this point, in face of heavy fire, he hurled bombs, killing and wounding some of the crew, then rushed forward, overcoming and bayonetting the surviving five gunners. His valour and initiative undoubtedly saved the situation and made possible the further advance to the objective.”

Essential Information.

Getting there.

The Visitor Education Centre is situated in the Canadian National Vimy Memorial Park. This is located near the village of Vimy about 5 miles (8 kilometres) north-east of Arras on the N17 to Lens. The memorial park is signposted just south of the village of Vimy.

Address: Canadian National Vimy Memorial, Route D55, 62580 Givenchy-en-Gohelle, France

For more information, click here.

St Teilo’s Church, now lovingly re-erected within the open-air precinct of St Fagan’s Museum of Welsh Life, is a remarkable testament to Wales’s medieval and 16th century heritage. Originally constructed in the early 16th century, this humble parish church was painstakingly dismantled, transported, and restored to its former glory — not least its dazzling wall paintings, which have been carefully recreated with scholarly precision. These vivid murals, brought back to life through meticulous craftsmanship, offer visitors a rare window into the devotional art and storytelling of the late medieval period. Stepping inside St Teilo’s, you’re transported back half a millennium, immersed in a world where faith, community, and artistic expression converged on plastered walls that still speak with vibrant colour and enduring power.